Collection Connection: Catherine Lee

Collection Connection: Catherine Lee

By Juan Zavala Castro, Education Assistant for Learning & Engagement

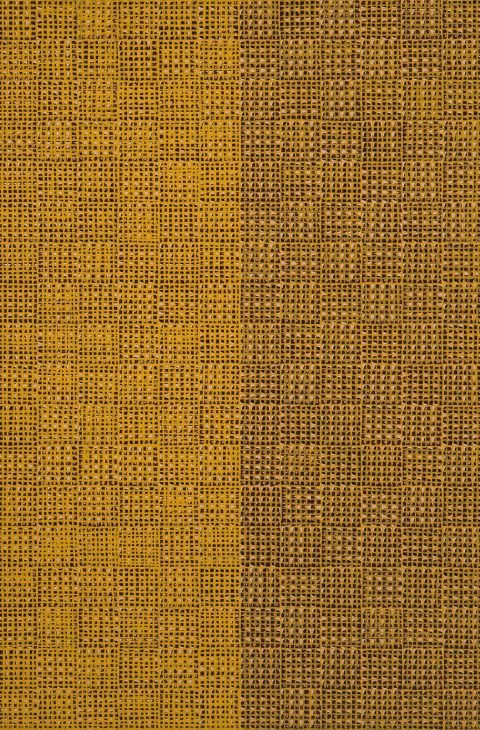

I first encountered the sculpture of Catherine Lee during my second year of the BFA program at Southwest School of Art. I remember seeing her work projected on the wall of the sculpture studio in a presentation on minimalist art. Lee’s work followed one of Donald Judd’s untitled “shelves” installations (likely meant to illustrate the dynamic nature of minimalism and form.) In Lee’s work, the forms were angular, seemingly referencing arrow heads or tools of the paleolithic era. Their shape and organization conveyed a sense of power. Meticulous placement with each form displayed at just the right distance from another caught my attention. I can safely say that the experience of seeing her work was one of those fabled “you’ll learn about it in college” moments. I found myself in that exciting time of arts education recognizing that realism was not the sole equivalent to artistic merit, a sentiment that (from my experience) many young artists feel when learning the basics.

I have found myself in the fortunate position of working in an institution hosting her work twice. As a BFA student, I witnessed the installation process and saw her sculpture activate the galleries. Now, at the McNay, I’m a different kind of insider. I experience her sculpture, like all visitors do, on the Museum grounds. Naturally, I had some questions for the artist, and I am thankful to have had the opportunity to interview Catherine Lee during the early stages of our unprecedented year in 2020.

What is something about your sculpture, Lewis (Hebrides 3) that the public might not know from reading the label?

Lewis is an island, or really half an island, along with the Isle of Harris, in the Outer Hebrides near Scotland. (Much like Haiti and the Dominican Republic, the two share a land mass.) The island is tiny, which makes this split all the more strange. Both are rich in history and amazing sites. The Isle of Lewis was my principal destination, as I’d wanted for many years to visit Callanish in person. Callanish, also known as Calanais, is a group of late Neolithic standing stones, which predates Stonehenge by about 500 years. There are many, many wonderful stone relics and cairns on the Isle of Lewis that are remote and mysterious. (You can even get a book from the local council that gives you just their geographic co-ordinates, to wander off in search of the more remote ones on foot.) With the Hebrides series, I hoped to reference these many important cultural sites, without simply imitating them. With Lewis I wanted to create a work that would encompass not the standing stones themselves, but rather that sense of looking out, of standing watch, and waiting. I feel that’s what Lewis does. It waits and watches.

Catherine Lee, Lewis (Hebrides 3), 2003. Bronze. Collection of the McNay Art Museum, Gift of Sean Scully. © Catherine Lee

You often work in large scale, either in size or scope of the project, what draws you to this size or types of installations?

I love the scale of one to one, viewer to artwork. There’s something interesting that happens when you go slightly up in scale from human size with an artwork, the dynamic changes and you’re taken to a slightly different perception, one where you can still relate intimately but you’re just a bit outmanned by the object. For comparison, I have four smaller bronze sculptures up at Mahncke Park, just opposite to the Botanical Gardens entrance, and there you get a very different scale relationship. Those works are intended to be less imposing, because the subject matter is very different.

The McNay’s bronze, Lewis, is part of the Hebrides series, all made in response to time I’d spent in the Outer Hebrides, off the coast of Scotland. This is a powerful place, full of ancient stones and history, and the work that resulted had to have reflected that. The smaller works in Mahncke Park have a different subject matter—Constancy. All are named using the word Constant, so Constant Sorrow, Constant Question, Constant Deliverance, Constant Trial. It’s a more playful concept and a very human concept, and therefore a human scale or even slightly under human scale helps achieve that tenor. Whereas, Lewis, a larger and more somber bronze at the McNay Museum is singular, like an island, and has a kind of gravitas that is appropriate to its subject, the windswept ancient Celtic Isle of Lewis.

When I look at your work, I am often taken back by the power that it possesses. The forms and materials seem to display very strong qualities. Am I reading too much into it, or do you intend for your work to have a specific aura?

Materials matter. I choose materials that are long lived, for the most part, and sculpture has that advantage. When I think of what’s discovered from ancient civilizations, it’s usually sculptural, three dimensional objects in durable materials: metal, especially those that oxidize very slowly, like bronze (think: Donatello), silver (Egyptian jewelry), gold (anything at Versailles), ceramics (think Mayan figures and bowls, the mysterious Cycladic figures, the Chinese terra-cotta figures found near Xi’an), or stone (Notre Dame Cathedral and many, many others, the Greek Laocoön and his Sons, and Celtic standing stones like Calanais, on the Isle of Lewis, by the way). Just for some examples.

My wish is to share my work with others, and that extends into the future, even into the far future. There is power in longevity. As to form, I think that the strength of a work lies in its subject matter. One might think that abstract art is without subject matter, but to the contrary, it is wholly dependent on content. Artwork without content is really just design, and that’s a different kind of work.

As you see your work become part of museum collections, do you think anything changes about that piece or series?

I love having my work go to museums, because there it is in the public domain. It belongs to the people who see it. I hope everyone feels this when they go to museums, that everything you see belongs to you because it does forever after… It’s gone into your psyche in some measure and because it may touch your heart or cause you to think, and because you can return again and again to see it. Art has a real purpose in our lives. It brings us together and it defines us as a culture, as a people. Artists make art because they have to. What people do with that art is up to each of us, as viewers, but I know for a fact that we support the arts just by going and looking.

I do believe that art is enhanced by its interaction with people. That’s what art is meant to do, to interact, and without that artworks are not whole, like music that’s been written but never gets played. In other words, if an artwork is not engaged in this way, on a very fundamental level it doesn’t fully exist if it doesn’t fulfill its purpose, which is to communicate. Art aspires to be a vessel of thought and understanding and knowledge and maybe even wisdom, you know, if we’re lucky.

Image of Catherine Lee by Courtney Chavanell.

Can you share your thoughts on the importance of museums and their collections as we settle into our new routines?

I find I spend a great deal of time visiting museums via the internet these recent days, in lieu of seeing works in person. You see, artists inform and fuel themselves by devouring art by others. The more I learn, the more I want to understand how things are made, and more importantly, why. It is a great mystery, why people make art at all, but more specifically what historical reasons they have for making the things they make. Some answers we will never fully know, but the journey through museums gives us our own sense of place and purpose, contextually. More and more museums are developing online presences – which is a welcome gift, especially now, when we need to protect ourselves and others by staying home.

Is there something you’d want visitors to know next time they see your piece?

What I would hope everyone understands is how lucky we are to have art museums to hold and protect our collective artworks. It is a huge responsibility, and a gift to us that they exist. There were seven Hebrides sculptures in this series. Lewis, Harris, Clach an Trushal, Scalpay, Scarista, Calanais, and Stornoway—all named for places within the Hebrides islands. All but one are in museum collections now, and as an artist, I am grateful to know that these works are in capable hands, and are there to be seen and considered by the curious, the learners, the thinkers among us.